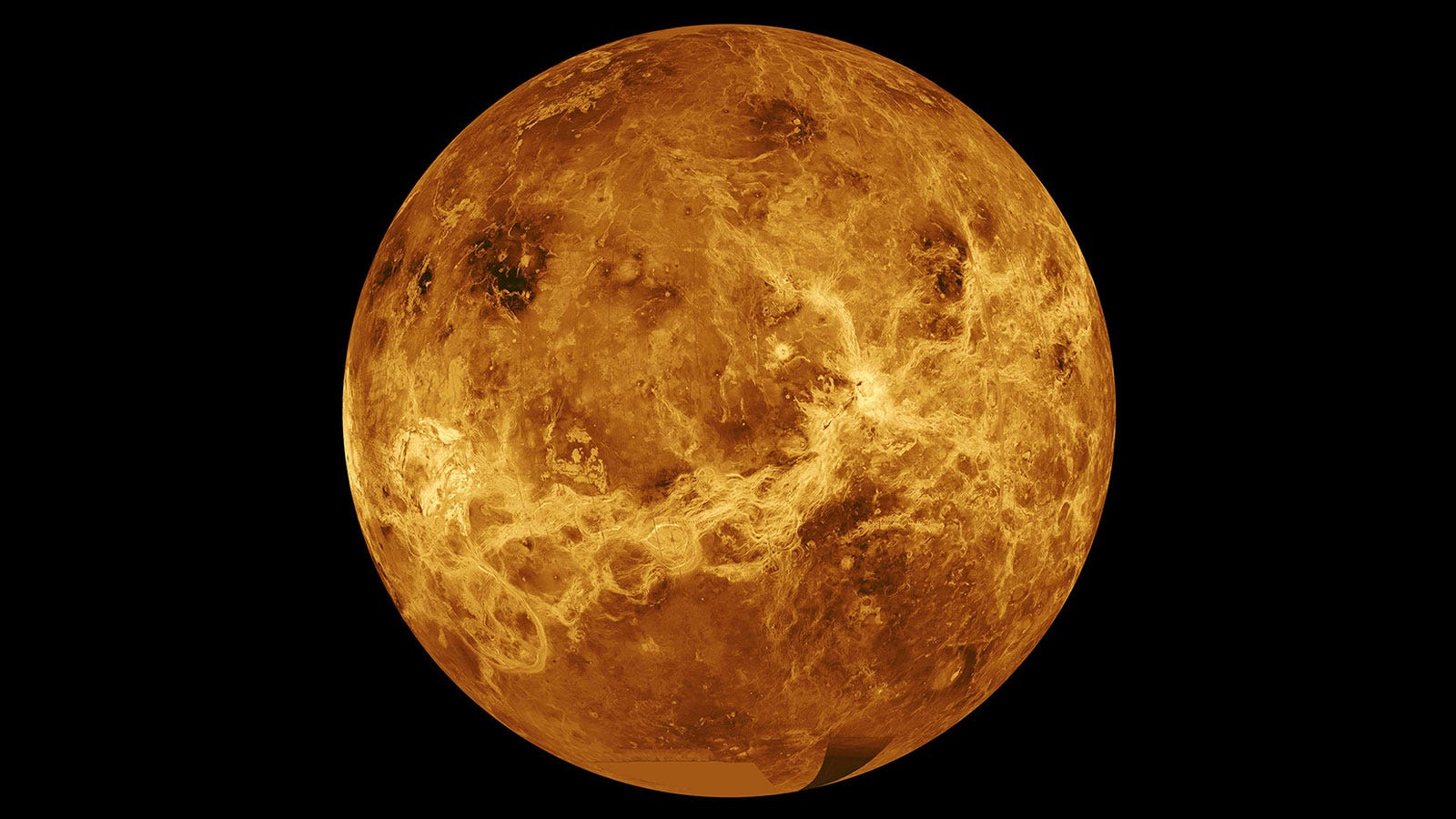

NASA/JPL-Caltech

- NASA is sending two new missions to Venus between 2028 and 2030, the agency announced Wednesday.

- The DAVINCI+ mission will plunge to Venus' "inferno-like" surface, while VERITAS will map the planet.

- The spacecraft could help scientists investigate how Venus became so hot and whether it holds life.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

More than three decades have passed since NASA last sent a probe to Venus.

But within the next nine years, two NASA missions will return to our closest planetary neighbor, according to the agency's new administrator, Bill Nelson.

Nelson announced on Wednesday that one mission, called DAVINCI+, will send a probe down to the Venusian surface to measure what Venus' atmosphere is made of. The other, a mission called VERITAS, will map the planet's surface in unprecedented detail.

"These two sister missions both aim to understand how Venus became an inferno-like world capable of melting lead at the surface," Nelson said. "They will offer the entire science community the chance to investigate a planet we haven't been to in more than 30 years."

Both DAVINCI+ and VERITAS are the winners of NASA's ninth Discovery program competition, which has funded 20 missions since 1992, including the Mars Insight lander, which is measuring quakes on the red planet. The losing competitors were missions to Jupiter's moon, Io, and Neptune's moon, Triton. Each winning Venus mission will get $500 million in NASA funding. The probes are expected to launch between 2028 and 2030.

Solving the mystery of Venus' hellish landscape

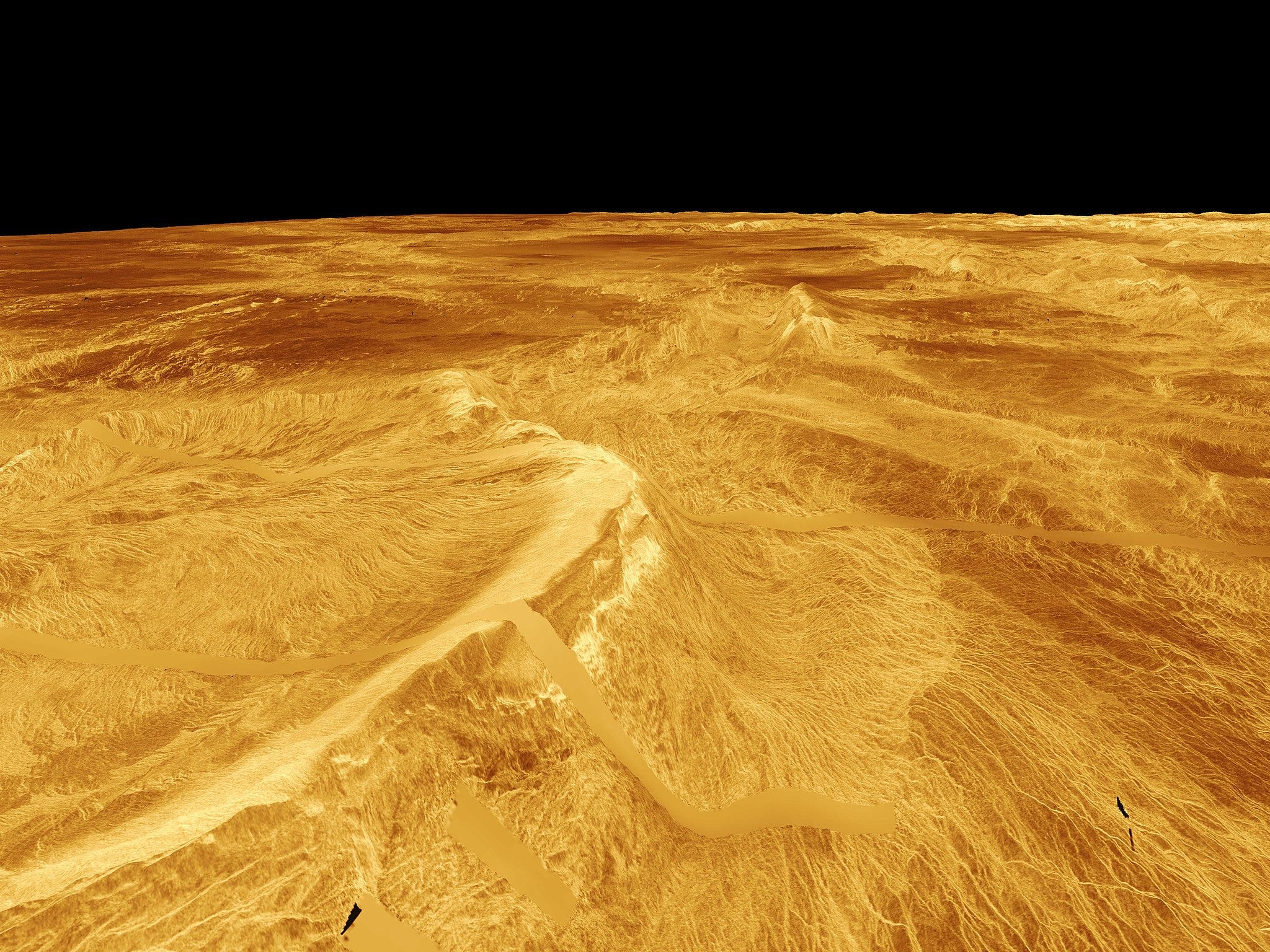

NASA/Banco de Imágenes Geológicas

Venus is Earth's hot and hellish twin. The two planets are similar in size, density, and surface composition, yet Venus is the hottest planet in our solar system. Its average surface temperature is a blistering 880 degrees Fahrenheit (471 degrees Celsius).

Nelson said the upcoming missions could help scientists figure out what causes Venus' extreme temperatures.

"We hope these missions will further our understanding of how Earth evolved, and why it's currently habitable when others in our solar system are not," he said.

DAVINCI+ stands for Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging. That mission will send a probe plunging through Venus' atmosphere to measure which gases and elements are present.

It will also investigate whether Venus ever had an ocean and take high-resolution pictures of geological features called tesserae. Tesserae are to Venus as continents are to Earth. Scientists hope to discern whether Venus has ever had tectonic plates like our planet.

VERITAS, meanwhile, will remain in Venus' orbit and map the planet's surface. The name stands for Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy. The mission should yield 3D reconstructions of Venus' topography and detailed observations the types of rocks that make up its surface. The scientists behind VERITAS also hope to study whether Venus has active volcanoes that could be releasing water vapor into the atmosphere.

The two missions come amid new debate among astronomers as to whether life is possible on or above Venus. Although the planet's carbon-dioxide-filled atmosphere would seem to make it inhospitable to life, a September study suggested the clouds surrounding Venus could harbor microbial aliens.

That's because researchers found traces of phosphine - a gas typically produced by microbes on Earth - in the upper reaches of Venus' clouds. However, a follow-up study suggested those trace elements weren't phosphine, but rather sulfur dioxide, casting doubt on the idea that Venus could be habitable.

These new missions to the planet could help settle that debate.

"It is astounding how little we know about Venus, but the combined results of these missions will tell us about the planet from the clouds in its sky through the volcanoes on its surface, all the way down to its very core," Tom Wagner, a NASA Discovery Program scientist, said in a statement. "It will be as if we have rediscovered the planet."

Jupiter and Neptune's moons will have to wait

To prioritize the Venus missions, NASA had to pass on two other proposals, both of which would have sent spacecraft to moons in the outer solar system.

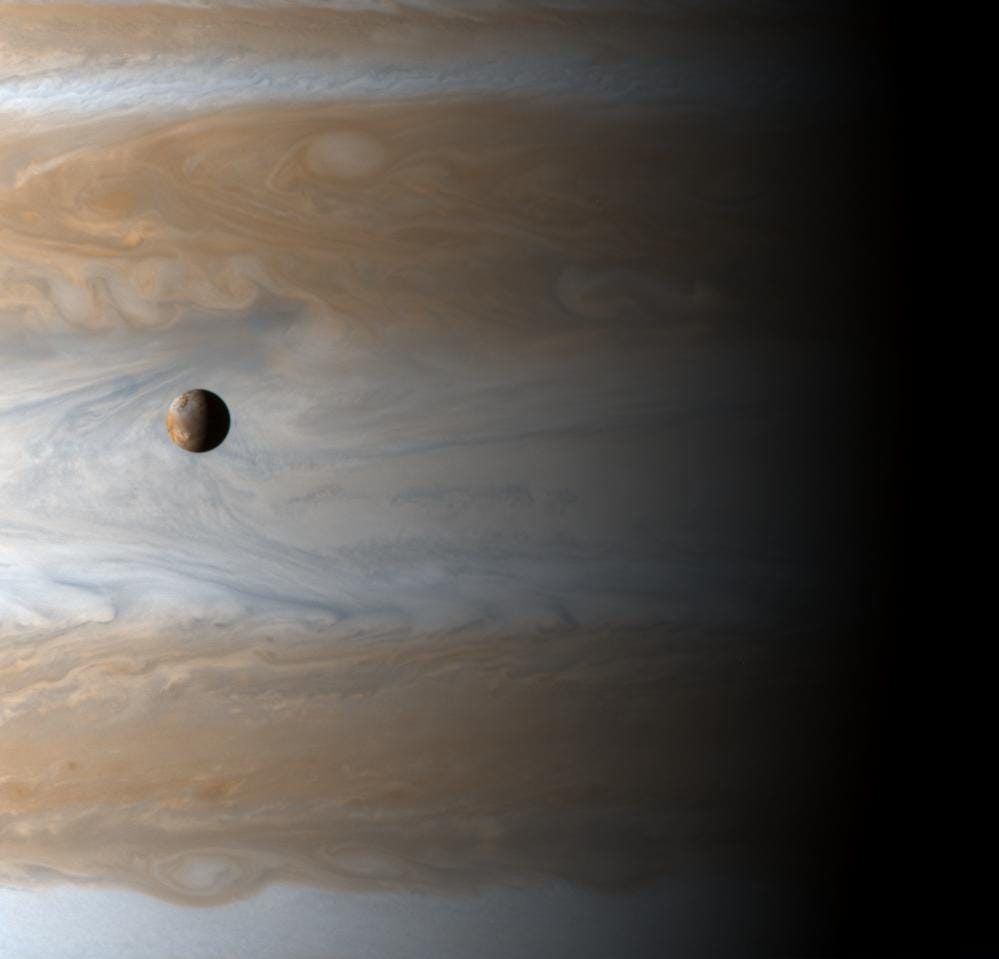

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

One of the Discovery finalists that NASA did not select is called the Io Volcano Observer. The proposal was to send a spacecraft to the most volcanically active place in our solar system: Jupiter's moon Io. The mission called for the probe to circle Io, flying in close enough to study its eruptions and look for signs of a magma ocean beneath the surface.

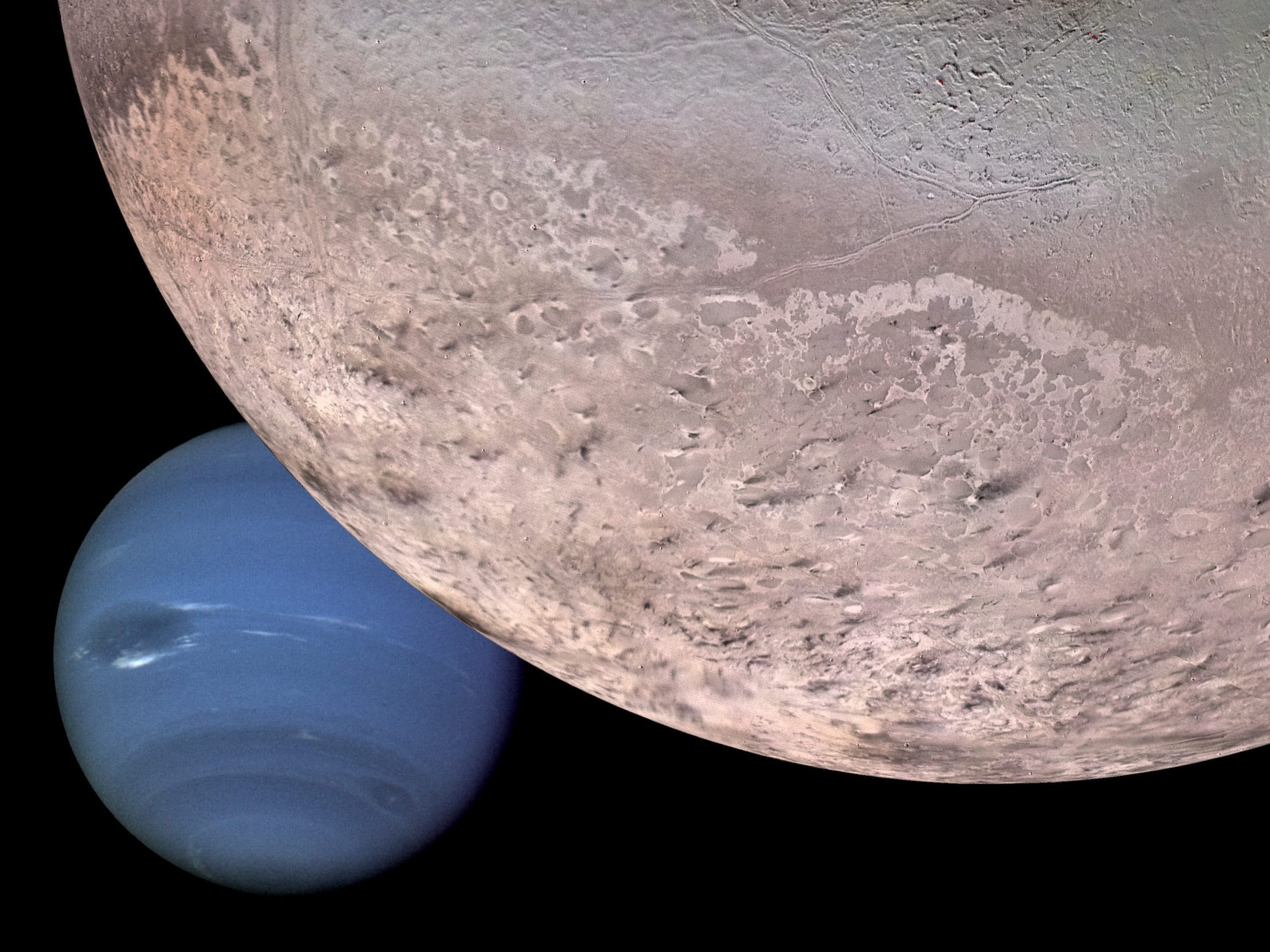

The second rejected mission, called Trident, would have explored Neptune's icy moon Triton. That ice world has an atmosphere that can create snow, and plumes of water may also erupt through its surface from a deep interior ocean. In one fly-by, Trident would have looked for signs of such an ocean, which could potentially host life.

NASA/JPL/USGS

This isn't necessarily the end for those mission concepts, but the researchers behind them will have to wait a few years before they can re-submit proposals to the Discovery program.

In a Q&A after the announcement, Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's associate administrator for science, said the two Venus missions had been through the Discovery process before without getting selected, and that their proposals were stronger because of it, according to SpaceNews' Jeff Foust.

"Those are the best missions. That's why we selected them," Zurbuchen said.